Sinking and loss of life

Unnamed fishing vessel

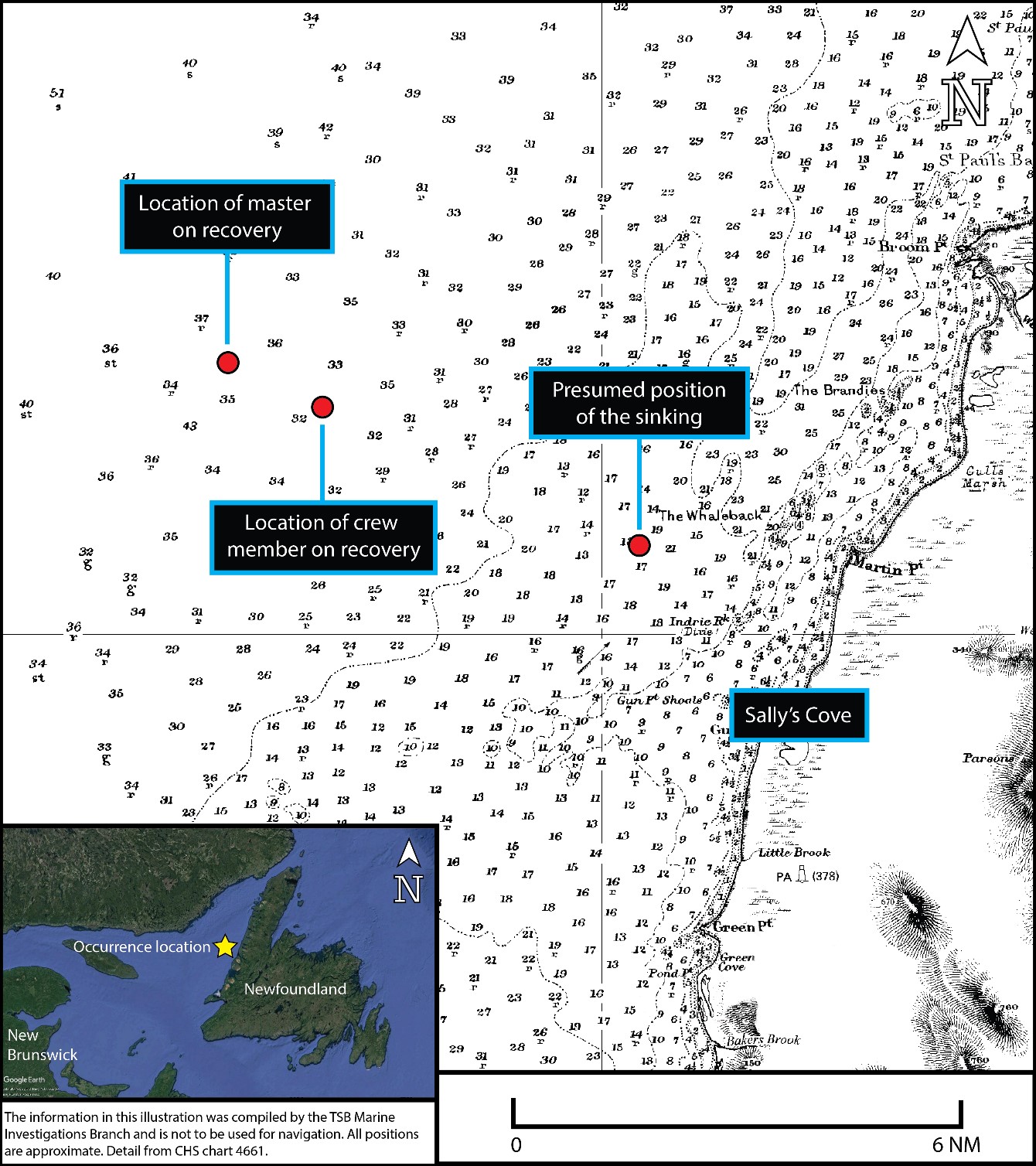

3 NM west-northwest of Sally’s Cove, Newfoundland and Labrador

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

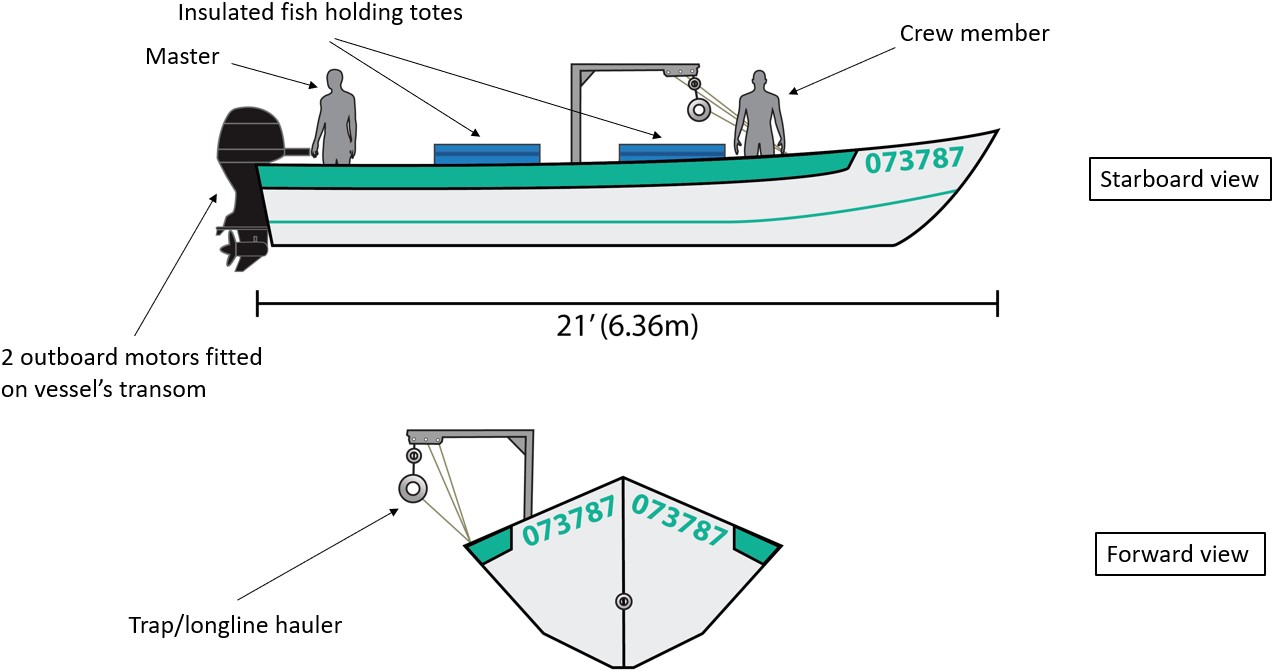

Description of the vessel

The occurrence vessel was a fibreglass fishing vessel of open construction that was 6.36 m long with a flat bottom (Figure 1). The vessel was powered by 2 gasoline outboard motors (60 hp/4-stroke and 50 hp/2-stroke) and had a trap/longline hauler located amidships. The vessel was carrying 2 insulated fish totes with tie-down lids. The unnamed vessel was not registered with Transport Canada (TC), but was registered with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (vessel registration number 73787).

History of the voyage

On 28 July 2020, at about 0500,Footnote 1 the fishing vessel departed Sally’s Cove, Newfoundland and Labrador, with the master and a crew member on board. The wind was from the northeast at 15 knots, the seas were 1.5 m, and the water temperature was about 16 °C. The sky was partly cloudy and the visibility was 10 nautical miles (NM).

The master and crew member ventured about 3 NM offshore to fishing grounds near a shoal known as The Whaleback to haul halibut longlines that had been set the previous day. There was effective cellular network coverage over the vessel’s area of operation. At about 0630, there were about 363 kg of fish on board. By 1400, the master and crew member had hauled 2 longlines and had 454 to 635 kg of fish on board. Both of the fish totes were full and some fish were stored loose at the bottom of the vessel. The master and crew member then started hauling the 3rd longline with the propulsion shut off, at which time the vessel’s stern gradually began to swing towards the incoming swell.

A large wave swamped the stern. The master immediately started the bilge pump and the 60 hp motor, and then attempted to turn the vessel’s bow into the waves, but was unsuccessful. The incoming waves flooded the vessel and it sank rapidly by the stern in presumed position 49°46.20′ N, 057°59.20′ W (Figure 2). Once in the water, the crew member, who was wearing a personal flotation device (PFD), held on to a portable gasoline container. The master, who was not wearing a PFD, held on to the lid of one of the fish totes by inserting his wrist through the rubber tie-down strap. The crew member attempted to use his cellphone to call for help but the device, which had been underwater, failed to activate. After a few hours, the master and crew member drifted apart and lost sight of each other.

At 1923, a relative of the master alerted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) that the vessel was overdue; it should have returned to Sally’s Cove more than 5 hours earlier. The RCMP called the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre in Halifax and a search and rescue (SAR) operation was launched. The ensuing offshore SAR operation involved the Canadian Armed Forces, the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), and CCG auxiliary vessels. The following resources were deployed:

- 2 CH-149 Cormorant helicopters from Gander, Newfoundland and Labrador

- 2 CC-130H Hercules airplanes and 1 CP-140 Aurora airplane from Greenwood, Nova Scotia

- 1 privately-owned airplane from Newfoundland and Labrador

- the CCG vessels Cape Roger, Cape Fox, and Cape Norman

A shore-based SAR operation was also conducted by the RCMP and a team of community members.

Air, marine, and shore-based SAR resources operated continuously throughout the night. On 29 July at 1035, the Cape Norman recovered the crew member, who was alert and still holding on to the gasoline container. Twenty minutes later, the master was recovered by the same vessel, but he was unresponsive. The master and crew member were transported to Rocky Harbour, Newfoundland and Labrador, and then medevaced by ambulance to the nearby hospital in Norris Point, Newfoundland and Labrador. The master was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Personal flotation devices

Not wearing a PFD on a fishing vessel is an unsafe practice that has been identified by the TSB repeatedly over the years. PFDs are designed to be worn at all times, permitting individuals to work without the restriction to movement of a lifejacket. However, many fish harvesters are resistant to wearing them, citing issues such as discomfort, the risk of entanglement, and the perception that it is not practical or normal to use them. Furthermore, it has been determined that fish harvesters often underestimate the risk of falling overboard.Footnote 2

Following the investigation into the 05 September 2015 capsizing of the fishing vessel Caledonian,Footnote 3 the TSB recommended that

the Department of Transport require persons to wear suitable personal flotation devices at all times when on the deck of a commercial fishing vessel or when on board a commercial fishing vessel without a deck or deck structure and that the Department of Transport ensure programs are developed to confirm compliance.

TSB Recommendation M16-05

As of 13 July 2017, TC’s Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations revised the requirements for the carriage of lifejackets and PFDs on fishing vessels. If an open-deck fishing vessel embarking on a Class 2 Near Coastal voyage, such as the occurrence vessel, does not carry lifejackets, all persons on board must wear a PFD at all times.Footnote 4

Risk-based regulations and industry initiatives have been developed to change behaviours and create awareness about the importance of wearing PFDs. PFD manufacturers have also improved PFD design to address fish harvester concerns about comfort and constant wear. Yet, many fish harvesters continue to work on deck without wearing a PFD, even when one is available.

In this occurrence, the crew member, who was wearing a PFD, survived after having spent more than 20 hours in the water. Although the master carried his own PFD on board the vessel, he was not wearing it at the time of the occurrence and did not have time to don it when the vessel sank rapidly.

Lifesaving and distress-alerting equipment

The Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations require vessels of not more than 12 m in length, engaged in Class 2 Near Coastal voyages farther than 2 NM offshore, to carry the following on board:

- one or more life rafts, or a combination of life rafts and recovery boats, with a total capacity that is sufficient to carry the number of persons on board; or

- the following equipment:

- i) an EPIRB or a means of two-way radio communication, unless the vessel is carrying on board an EPIRB required by the Navigation Safety Regulations, 2020, and

- ii) if the water temperature is less than 15°C, an immersion suit or an anti-exposure work suit of an appropriate size for each person on board.Footnote 5

Under these regulations, vessels such as the one involved in this occurrence are required to carry some combination of the equipment listed above, which may not necessarily include an emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB). This device transmits an emergency signal, either automatically or when activated by the crew, to immediately alert SAR resources and initiate rescue efforts.

The occurrence vessel did not have a life raft, recovery boat, or EPIRB on board. Although both the master and the crew member were carrying cellphones as a means of two-way radio communication, neither of them were able to use their phones to alert authorities during the occurrence. At the time of the occurrence, TC accepted cellphones as a compliant means of two-way radio communications on fishing vessels less than 8 m in length operating in Sea Area A1,Footnote 6 where there was sufficient reliable cellular network coverage to enable their immediate use, which was the case in this occurrence.

Previous TSB investigationsFootnote 7 have found that carrying an EPIRB can contribute to saving crew members’ lives. When a vessel’s EPIRB is activated, it transmits a continuous distress signal indicating the vessel’s precise location. With this information available to other vessels or SAR resources, assistance can arrive on scene more quickly, greatly increasing crew members’ chances of survival.

From February 2010 to July 2020, the TSB received reports of 15 occurrences (resulting in a total of 34 fatalities) involving the capsizing or sinking of small fishing vessels less than 12 m in length that were not equipped with an EPIRB. No distress signal was received by other vessels or SAR resources in any of these occurrences.

The TSB has previously recommended that small fishing vessels carry an EPIRB or other appropriate equipment that floats free, automatically activates, alerts the SAR system, and provides position updates and homing-in capabilities.Footnote 8 Since this occurrence, the Navigation Safety Regulations, 2020Footnote 9 have come into force with additional requirements.Footnote 10

Related occurrences

M18A0303 (Kyla Anne) – On 18 September 2018, the 11.5 m fishing vessel Kyla Anne, with 3 crew members on board, capsized while returning to port after a lobster fishing trip about 1 NM north of North Cape, PEI. Only 1 crew member survived the capsizing. Neither PFDs nor an EPIRB were on board at the time of the occurrence.

M18A0078 (Ocean Star II) – On 12 May 2018, the 8.69 m fishing vessel Ocean Star II, with 3 crew members on board, capsized while hauling lobster traps approximately 0.05 NM (100 m) from the shoreline at Colindale, Nova Scotia. All 3 crew members survived the initial capsizing, but only 1 crew member survived after being in the water and making his way to shore. The crew members were not wearing PFDs, and the vessel did not have an EPIRB.

M18A0076 (Unnamed fishing vessel) – On 05 May 2018, a 5.79 m unnamed fishing vessel was found capsized 0.04 NM (74.1 m) northeast of Beach Cove in Port Medway, Nova Scotia. The vessel’s 2 crew members were recovered and pronounced dead. The crew members were not wearing PFDs, and the vessel did not have an EPIRB.

M16A0327 (Pop’s Pride) – On 06 September 2016, the 6.7 m fishing vessel Pop’s Pride, with 4 crew members on board, was reported overdue after it did not return to St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. Two of the vessel’s crew members were recovered and pronounced dead, while 2 others were not recovered and are presumed drowned. The vessel was not equipped with an EPIRB and, when it was recovered, no safety equipment was found on board.

M14P0121 (Five Star) – On 12 June 2014, the 8.69 m fishing vessel Five Star capsized and sank when the crab catch stowed on deck shifted while underway in adverse sea conditions near Kelsey Bay, BC. The master and crew member on board abandoned the vessel. It was not the practice for the crew to wear PFDs during normal fishing operations. The crew member swam to shore, but the master was not recovered and was presumed drowned. The vessel did not have an EPIRB.

TSB Watchlist

The Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada's transportation system safer. Commercial fishing safety has been an issue on the Watchlist since 2010.

TSB safety issue investigation into fishing safety

In 2009, the TSB initiated a safety issue investigation into fishing safety. The safety issue investigation identified that, despite many safety initiatives, unsafe practices continue. As seen in this occurrence, gaps remain with respect to safe work practices and adequate regulatory oversight, as well as the carriage and use of lifesaving equipment, such as PFDs, immersion suits, and emergency signalling devices.

Safety messages

The TSB continues to see PFDs not being worn by crews in fatal fishing vessel occurrences such as this one. Wearing a PFD can mitigate the adverse consequences of being immersed in water and increase a person’s chances of survival until help arrives. Fish harvesters need to take responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their crews by ensuring that PFDs are worn when working on board their vessels.

Getting assistance quickly can also be crucial to survival. It is important that fish harvesters carry a distress-alerting device, such as an EPIRB or personal locator beacon, that can automatically broadcast a signal to indicate that a vessel or an individual is in distress, provide a precise location for search and rescue, and enable a timely response.

Many fish harvesters opt for a cellphone as their means of 2-way communication in an emergency, but it is essential that they be aware of the limitations of cellphones in these situations. Furthermore, regulations now require vessels less than 8 m in length operating outside sheltered waters to carry a waterproof, portable VHF handheld radio with DSC capability if there is no EPIRB or personal locator beacon on board.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .